AI, agency and choice

You know there’s a lot of talk about artificial intelligence – or AI – these days. Just this week another high-profile voice was added to the choir when Steve Wozniak, one of the founding members of Apple, joined in to voice his concern about the dangers of AI.

At the same time, companies all over the world and across the spectrum, from Google, Facebook and Microsoft to nickle-and-dime startups, promise a new dawn of both life and technology driven by smart machines – the message is that soon nobody will have to make dull choices because computers will be intelligent, and they’ll know you like a friend and make choices for you.

And now I’m going to add my nasal voice, too – but my angle on this is going to be a little different, as per usual.

I’m not that kind of expert but I’m not actually sure we’re going to see strong AI in machines anytime soon – but the thing is, as far as these issues are concerned it doesn’t matter. We’re perfectly able to create problems, even danger, with the computers we have now, and we’re also already seeing some boundry-breaking moves in choice and decision-making.

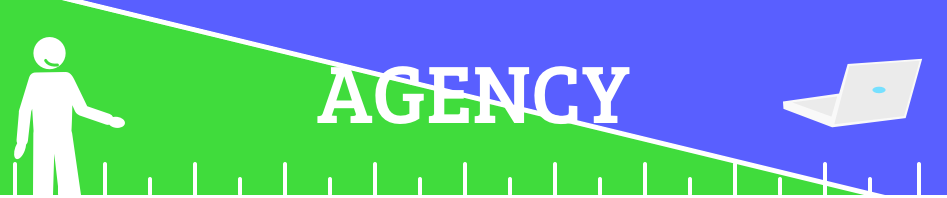

The reason it doesn’t matter is that the issue at hand isn’t how intelligent a computer may be – the issue is what agency it has. Now, as an advisor, helping businesses work and thrive in the modern world, I’m not about to scare everyone away from what is clearly right in front of us. Instead, I am going to talk about some of the considerations we should be having to make the most of it.

When talking about agency we’re actually able to deploy a sliding scale that looks a bit like this:

We’ll want to find out where we reside – or wish to reside – on that scale. “We” here meaning anyone with a product or service, but also, crucially, the users of said product/service. It’s important to note that there isn’t anything inherently wrong on either end of the scale. Some things are best left to be people-decisions, some things machines can handle just fine, and many things will work best with a blend of human and machine decision-making.

But we need to select that level of agency deliberately.

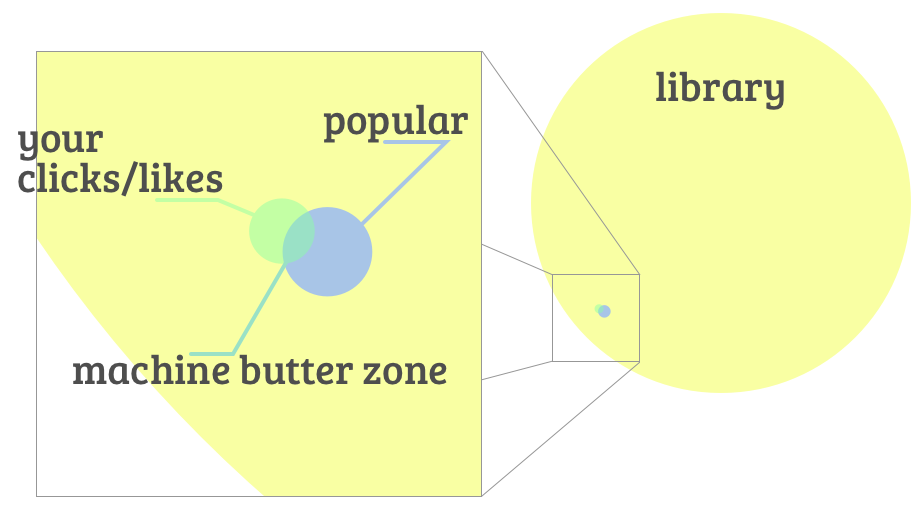

Let’s grab an example from right now: Your news feed. You know, whatever that might be – a selection of newspaper websites, an app, Facebook or whatever. We all know there’s just too much information/content out there, but there are different ways of dealing with it. For example, Facebook already filters your stuff – the filters assume you’ll want more of the same so if you interact with things you get more of whatever the system considers “the same” (the formula for which is unknown). The effect of this kind of filtering is additive exposure for a reverse funnel of content; you’re shown what’s “popular” with you, and you interact with some of it, and are shown more of that subsection, and so on.

The same reverse funnel effect is seen anywhere there’s a popularity algorithm in place. Check out your music streaming service of choice – there’s a very small sliver of the total library that gets massive exposure, and then it reverse-funnels off and all of the rest, comperatively, gets almost none (for example, some 4 million songs on Spotify, about 20% of its library, have never been played). People are presented with some form of “popular now” selection, and any interaction with this selection narrows it.

On the other hand there’s feeds like Twitter – it doesn’t get filtered algorithmically but you can curate it by way of your choice of sources, and then it’s up to you to click or not click. Most online news services – aggregated or individual – also don’t filter. Here the choice is all yours, and you have to keep choosing every time you open the feed.

Landing in between and putting curation tools front and center are services like Feedly, where you create collections of sources, save stories etc. An even more powerful curation tool is the startup Cronycle which is intended for people who have to navigate feeds and sources professionally and in groups – say, for journalistic work, or researching your field of work, seeking inspiration and so on.

What we’re seeing is different takes on the issue of agency, and the intelligence of the computers doesn’t much matter. Even if they really are super-smart the issue is still agency: What level of decision is yours, and what resides with the service. We know we can’t read, watch or listen to everything, something is going to get sorted out – we just need to be aware of how this sorting happens, and who the agent is in it. As I said, there’s nothing wrong with either alternative; it’s all about choice. What we need to do – in a wholly undramatic, constructive, even utilitarian way – is figure out how, when and why we want machines, smart or not, to help us make better decisions.

Whether we make and sell them, or just use them.

brain illustration via Wikimedia Commons – graphics by Jesper W. of CPH