New or “old” customers?

If you are one of the people who follow me ’round the social media – like LinkedIn, Facebook or Twitter – or even read these articles now and then, you might have noticed this little tidbit which I come back to quite often:

“as a rule-of-thumb, some 80% of the lifetime revenue of any given company comes from just 20% of its customers”

This is an interesting statistic, based on investigations in many parts of the world. For example, Copenhagen Business School carried out such an investigation – incidentally, that particular one found that, for certain sectors, the figures can go as far as 90:1, meaning that 90% of the revenue comes from just a single procent of the customers.

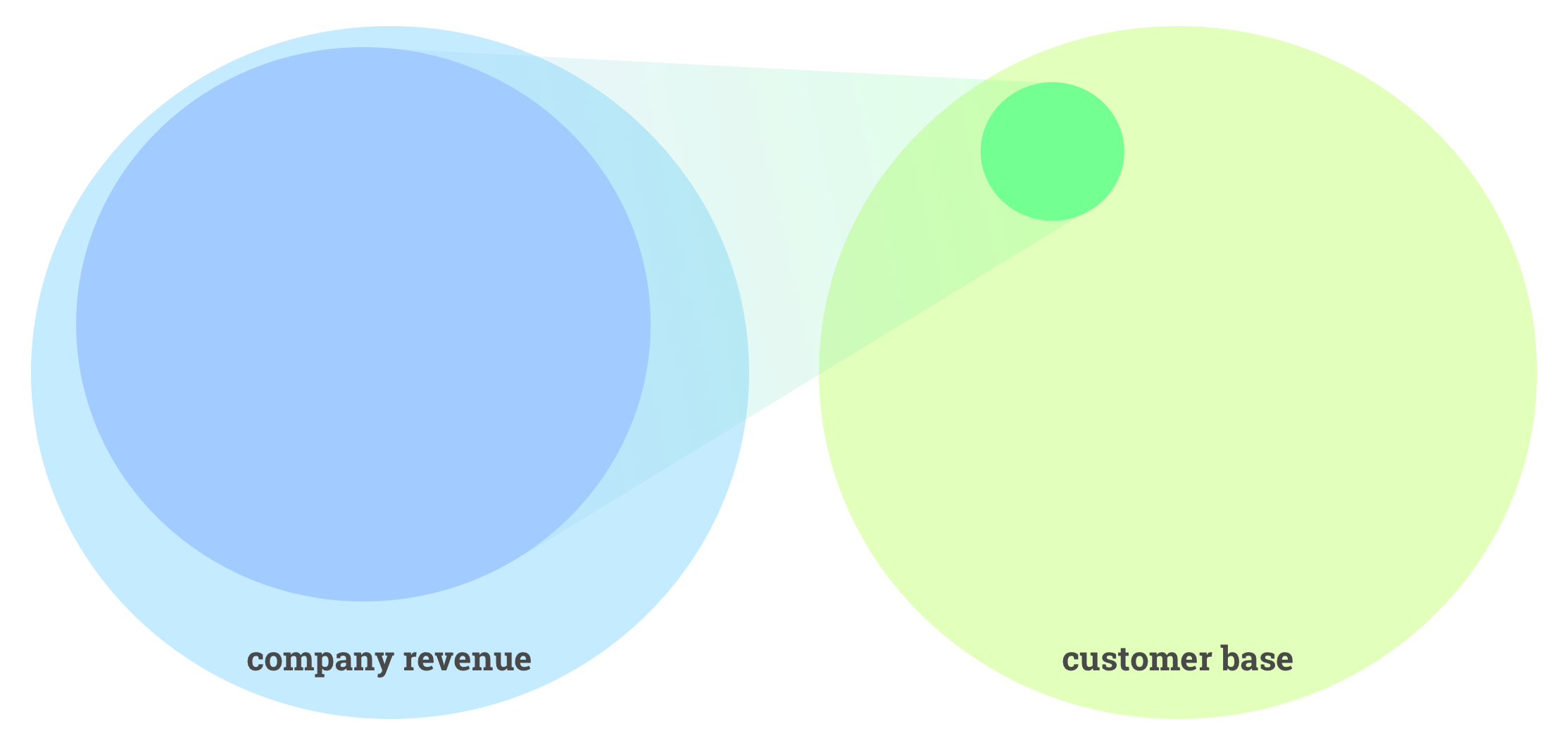

But numbers tend to be a bit abstract so let’s go ahead and visualize it:

Looking like that it’s pretty clear – and what’s also pretty clear is that those customers in the little green circle are really interesting. Can we identify those people? Why yes, we can, and it turns out they’re return customers – your most loyal customers, in other words. It’s not that hard to understand if you look at the math; of course there may be significant differences between what actual people buy, individually – and we should pay attention to this, too – but given an average customer she doubles her value when she comes back for her second visit. This dramatic increase doesn’t continue, of course, but every time she returns her value further increases, while the one-timer customer’s value obviously doesn’t change over time.

As I said this is a rule-of-thumb but it’s pretty robust: – for most companies the most valuable customers are the loyal ones.

See, that’s a pretty good reason for us to care whether our customers are loyal, and about how we might go about getting more people like that in the store – but we aren’t actually done looking at this particular kind of customer. If you’re a really persistent fan (in which case, thank you!) you might have stumbled upon this other little ditty I also bring up repeatedly:

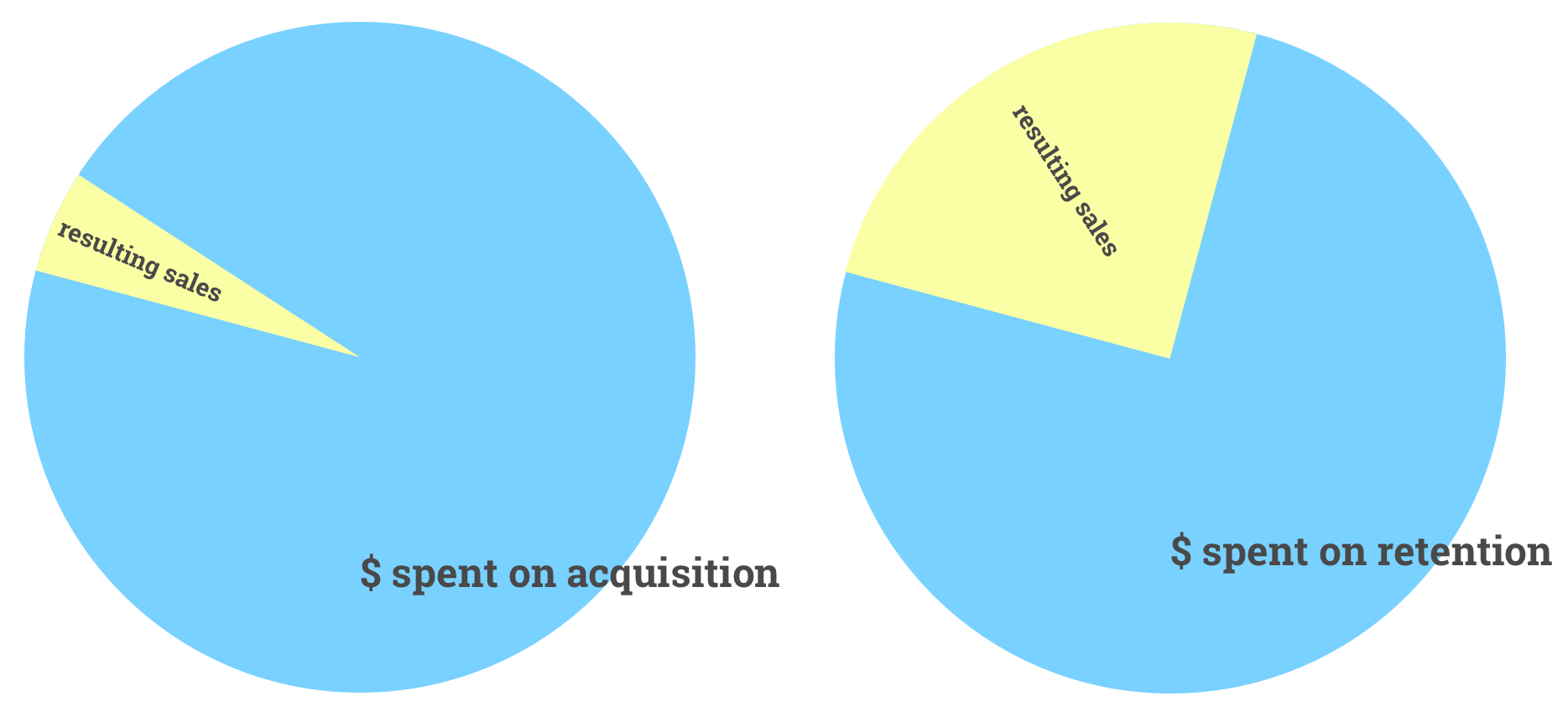

“the cost of acquiring a new customer is 4-6 times greater than making a sale to an existing customer”

Again with those blasted abstract numbers – let’s break out the circle machine again for a bit of visualizin’:

The visuals pretty much speak for themselves – and again, this is quite a robust result; it’s much more expensive to persuade a “stranger” to shop with you than getting someone who already has to do it again. Assuming, of course, that you provide a good customer experience.

And right there the central point to all of this appeared all on its own: – giving your customers a good experiences pays off (really well, in fact).

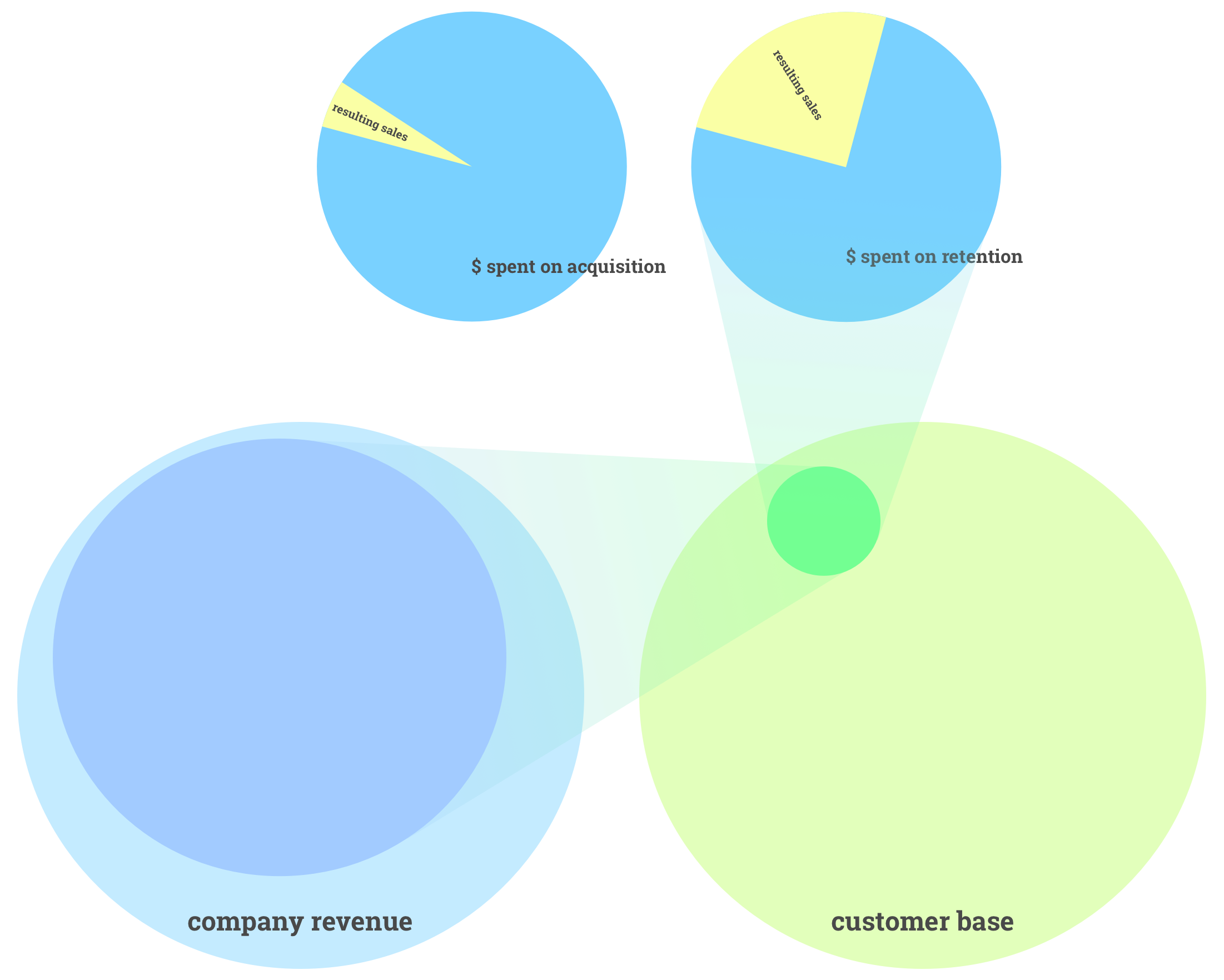

Let’s combine those two graphics:

There’s a direct line from customer satisfaction to a significant part of your revenue. Did you know that? – and are you sure your company is paying the attention an economic factor of this magnitude calls for? Think about how far any sensible business management would be prepared go – and how much they’d be prepared to pay – to, say, increase sales a few percent, og save a few percent on the next quarterly. Then look at that graphic again, does it seem like something anyone can afford not to take very seriously indeed?

A great deal of money is spent acquiring new customers – typically by way of advertising budgets which grow year after year – and at the same time businesses are trending towards trying to save on customer service by outsourcing, personnel cutbacks (number and training), shuttering departments etc. Simply put, we’re trying harder and harder to bring in the customers, while stifling efforts to secure the quality of the experience they’ll have once we get them in the door.

Turns out this isn’t a very good idea at all. Perhaps more businesses should go talk to someone about that customer experience stuff?