Nudging

OK, now that I have your attention, by virtue of mentioning one of the hottest buzzwords of the day (other than Big Data) I thought I’d take you through a brief explanation – as it’s so often the case with buzz concepts, it can get a little confusing as everybody scrambles to shoehorn the latest whassamabobbit into their reputation, if nothing else.

In other words: What is nudging?

I recently took part in a user experience outing for EKF (under the auspices of Brugercentrisk), where – among other things – Andreas Maaløe of ISSP gave a great introduction to the concept of nudging. Since you, dear reader, weren’t there (probably), here’s my version of that for your benefit:

“Nudge”, meaning “a gentle push”, is in fact just that – in terms of behavioural nudging, the term was coined by Thaler and Sunstein in 2008, and it covers the principle of influencing people to behave in a desired way by any means other than the obvious, those being by aversion (making not doing it unattractive), incentive (offering a reward) or prohibition (just what it sounds like).

Those obvious methods deserve a bit of attention first because a certain, basic understanding of them is necessary to get on with this. The way aversion, incentive and prohibition largely work is at an explicite level, as in, it comes to our attention somehow that there’s something to be gained by doing this-or-that thing – as such, they’re based on the notion that people function primarily through explicit, mostly rational decision making.

That’s all well and good for certain things but we’ve come to understand, scientifically, that this doesn’t actually cover very many human activities. There isn’t that much we do which is completely, or even mosty, explicit and rational.

It turns out that we’re actually mostly irrational.

It just doesn’t seem that way to us because one of the major functions of consciousness is to make up explanations for our behavior that we can live with – some call this “making excuses” but that’s selling it a bit short, and it will also tend to exclude all the times we do this without being aware of it. I’ll go with post hoc hypothesizing.

The reason this is important is the “post hoc” (litterally “after this”) part, i.e. our rationality often comes into play after the fact. This means it’s a bit too late to influence behavior in that instance.

And that’s where nudging comes in.

Actually, even though this explicit term is relatively new, the idea behind it isn’t – if you’ve read my wee manifesto on “Activity Centered Design” from 2009, you may notice the familiarity, for example (I won’t go into it much here – ask me), and the idea of addressing instincts is old-hat to the advertising industry, too.

So that’s the concept (very briefly), but how does it work practically?

Well, as I said, it’s all those non-explicit means that go into nudging – but let’s take a few examples:

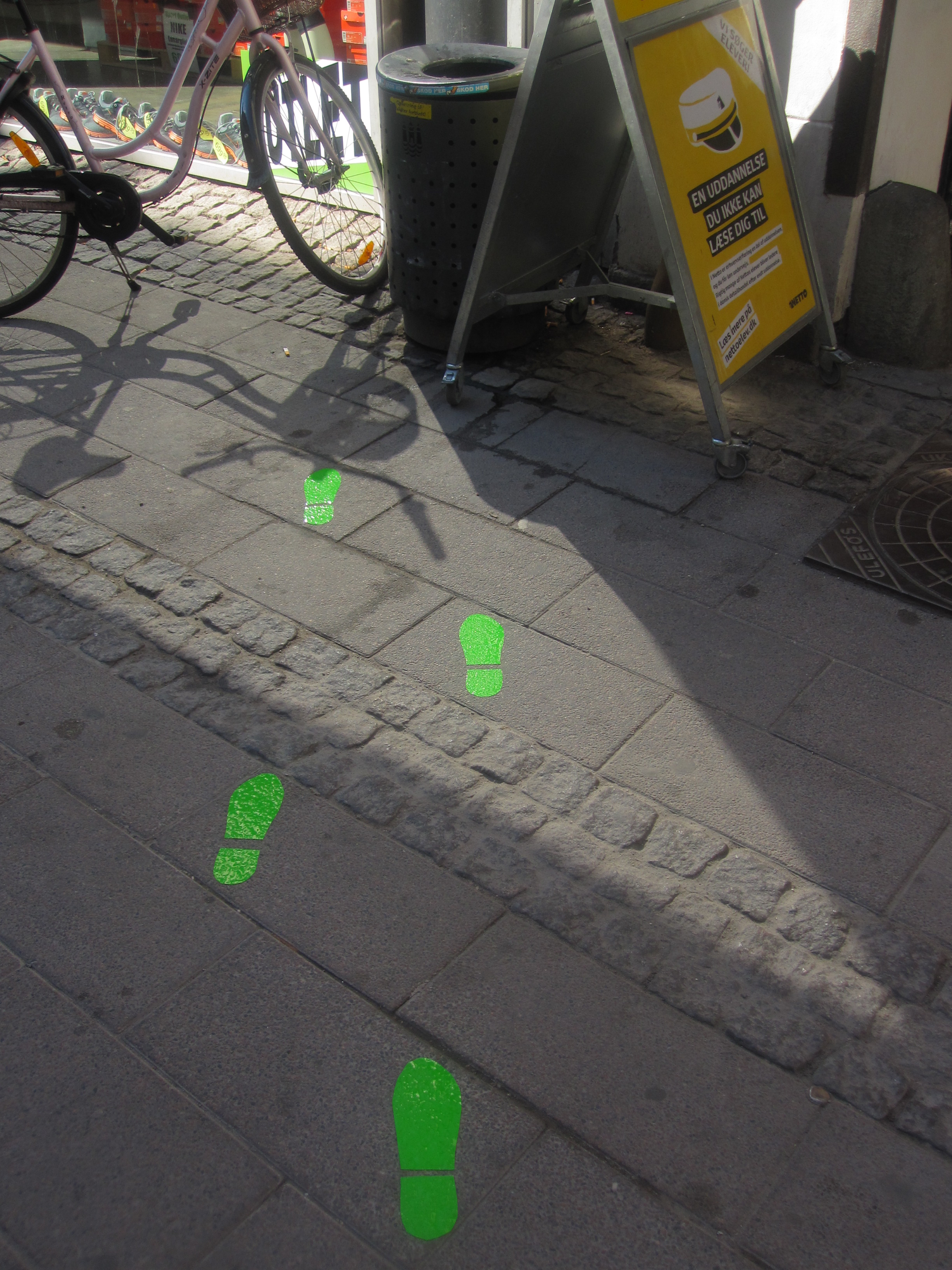

The image on the right is from a project in Copenhagen – the idea is that those very visible foot prints leading to the waste bin heightens people’s awareness of it, subconsciously activating the knowledge of what trash is, and what to do (or not do) with it. In consequence, people will be less inclined to litter – the project did, in fact, reduce street littering by some 40% according to I Nudge You.

In an effort to battle erroneous tax return information, nudging principles have been tested in the UK – such tactics as social cues like “9 in 10 people in Britain pay their tax on time”, among others, drove savings of GBP240.000,- in Manchester and were estimated to potentially collect GBP160 million in outstanding tax revenue if implemented countrywide.

Many different entities have had great success with reducing food plate size as a nudging tactic for reducing both food intake (in an effort to battle obesity and promote health) and food waste. This works both on an organisational level and individually – replacing the dinner plates with smaller ones at home, one can nudge oneself to eat less, and of course, reducing food waste is becoming quite a thing.

The reason this last one works is that we tend to eat in “units” – one plate of food, one bowl of soup, one slice of bread or one cupcake (or 2 or 3 but very rarely 1.2, and even more rarely 0.6 cupcake) – rather than eating until we’re sated and stopping. This is a very good example of a completely automatic behavior which can be extremely hard to battle at the explicit or rational level; most people will protest that they do this, because we generally like to see ourselves as in control.

This brings me to the part where we have to talk about the risks and limitations of this concept, because of course it has those – this, like our other methods, is a tool, and no tool does every job.

Perhaps the most obvious thing to be aware of you can (almost) identify just by looking at the buzzword itself – nudge. A gentle push in a desired direction. Think about this in terms of walking down main street with your friend, who spots a shop he’d like to go into. In an effort to do so, he gives you a gentle push in the direction of the shop’s entrance, and – in the success-for-him case – you go in.

However, imagine that you, without noticing what he’s trying to do, resists the nudge and keep on straight ahead, and then imagine if he keeps nuding you, just *bump*, *bump*, *bump* – you’ll probably get annoyed, right?

And then, when he says “sorry, just wanted to go in there”, you might say “well you could have just said so” – nudging can turn into nagging real quick, and if you don’t stop before then and change tactic to openly declaring your intention (or seizing your swaying attempt altogether), you may well create a rejection.

Another important thing to consider about nudging is the kind of behavior change you’re looking to create. Not all behaviors respond equally well to this method, and most importantly, nudging has proven very inadequate for creating permanent changes in behavior.

This can actually be a good thing, both because it lets you use this method when relevant, and then you won’t have to “de-program” the behavior later – also, it makes testing for effectivity possible, since you can turn the nudging on and off and measure the difference.

But it also means that if the thing you need to spread, the behavior, position or whatever, should be something that people take to by themselves eventually, nudging them there most likely won’t work – and that’s because short term learned behavior is the domain of the rational, explicit mind.

The final major thing to consider is that these methods, with all their subtlety and subconscious responses, can very easily be seen as manipulative, something most people react very negatively too – mostly even if you’re trying to “manipulate” them into something beneficial. Again, we like to think that we’re in control, and if we feel our personal space being invaded by some hidden force that can make us act without informing the conscious mind, we can get pretty upset.

Of course, you don’t have to work out completely on your own if using these techniques are for you – just ask someone to help you. Like me, for example.